Stained Glass before 1700 in American Collections: Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern Seaboard States

From the Introduction to the 1987 publication

With publication of Checklist II of “Stained Glass before 1700 in American Collections,” we conclude the catalogue for the mid-Atlantic States. Also included in this segment are the southeastern seaboard states. A third part will comprise collections in the rest of the United States, while the fourth segment will contain the uni partite panels, commonly known as silver stained roundels. The fourth part will also include an addendum of panels not published in the first three parts, whether through ignorance, because of inaccessibility for examination, or because they are additions that have been made in the interim to collections already catalogued.

With publication of Checklist II of “Stained Glass before 1700 in American Collections,” we conclude the catalogue for the mid-Atlantic States. Also included in this segment are the southeastern seaboard states. A third part will comprise collections in the rest of the United States, while the fourth segment will contain the uni partite panels, commonly known as silver stained roundels. The fourth part will also include an addendum of panels not published in the first three parts, whether through ignorance, because of inaccessibility for examination, or because they are additions that have been made in the interim to collections already catalogued.

As in Checklist I, Checklist II includes stained glass in both public and private collections. It does not contain glass considered by the American Committee of the Corpus Vitrearum to be forged, though when opinions differ pieces may be included because further study is needed to arrive at a consensus; and it simply lists the many fragments, whether single pieces of painted glass, or pieces made up into decorative panels, though the rare Byzantine fragments in Dum barton Oaks deserve further study. Also omitted are pieces currently on the art market, although it is hoped that they will become part of a permanent collection and thus be included in the Addendum to Checklist IV.1 It is the intention of the authors to provide a preliminary overview of glass in American collections and a summary of basic data for later use in the expanded catalogues. Under the Corpus guidelines, these catalogues will be published as fascicules organized according to the geographic location of the collection.

By far the largest single collection included in this segment is that amassed by the late Raymond Pitcairn, now owned and exhibited by The Academy of the New Church at the Glencairn Museum in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. Unlike the holdings of The Metropolitan Museum of Art ( already included in Checklist I), which cover virtually the full range of dates and geographic distribution recognized by the Corpus Vitrearum, the nearly 250 pieces in that collection are primarily of French origin and mostly before 1300 in date. Until the recent exhibition of a portion of the collection at the Cloisters and special receptions at Bryn Athyn for organizations such as the International Corpus Vitrearum and the International Center of Medieval Art, the Pitcairn collection was the great enigma of medieval stained glass in America. It had been closed to all but a few specialists since Raymond Pitcairn’s death in 1966.

Another specialized collection contained in this segment is the heraldic glass from the Dixon estate, Ronaele Manor in Elkins Park, that is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Broader in the subjects and periods represented are the holdings of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, which nonetheless seem to reflect the anglophile traditions of that region. Much more general in scope are the sizable collections, with more than fifty pieces in each, in The Art Museum, Princeton University, and in the Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore. The richness of the glass collections in these museums could be anticipated. Less well known is the Gellatly Collection, now in storage in the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Several fine pieces in the Baltimore Museum of Art also came as a surprise. Stained glass in southern collections, much of which has never been published and some of which is still in private hands, is also little known: a splendid German Saint Nicholas window is at the Morse Gallery in Winter Park, Florida, and the impressive French Mystical Fountain window is at Bob Jones University in Greenville, South Carolina. The latter has been traced to the chateau of Boumois, near Saumur on the Loire river, and it was mentioned briefly by Sterling, but definitive studies on all this glass are yet to be undertaken.

The individual preferences and personal tastes of the founder collector are strongly evident in the collections included in this segment of the checklist. More collections in the mid-Atlantic and southeastern states were founded by individuals, and more remained for long periods in private hands. Giants in the history of American collecting like William Walters and his son Henry, Peter A. B. Widener and his sons and grandchildren, and Raymond Pitcairn dominate the now public collections in this area of the country. To a lesser extent solid patrons of the arts, like John Gellatly, William Corcoran who was aided by Senator William A. Clark, George Grey Barnard, and Saidie A. May, have made their influence felt. Less well known, but hardly less active in the area of glass collecting, are those responsible for the collections of the South, such as Bob Jones II, or Hugh and Jeannette McKean.

William Walters began acquiring early American paintings and a few salon pictures in Baltimore around 1855. His interests broadened to include contemporary French art when, in 1861 being a southern sympathizer, he went to Paris for the duration of the War between the States. It was his son Henry, however, who further broadened the focus of the burgeoning collection by adding, among other areas, the superb medieval manuscripts, treasury arts, and stained glass. Some thirty-five examples of stained glass were purchased in the first decade of this century. Henry Walters also built an art gallery adjoining his home that was open to the public a few weeks out of the year. Upon his death in 1931, the collection and the gallery were left to the city of Baltimore but most of the stained glass remained in storage until it was first shown, for a brief time, in a special exhibition in 1960. Since the addition of a new wing two decades ago, the best thirteenth-century French glass has been installed in natural light, but the greater part of the collection remains in storage. Peter A.B. Widener of Philadelphia collected art throughout his lifetime and was followed in this interest by his sons, George and Joseph. George died on the Titanic together with his own son Harry Elkins, a precocious rare book collector; Joseph inherited control of his father’s collection, which had been placed in trust, upon the latter’s death in 1915.9 Joseph built the palatial Lynnewood Hall, patterned on Versailles, in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania, to house the collection. In addition to old master paintings and sculpture, the Widener collection was a treasure trove of decorative arts, containing esteemed tapestries, furniture, extraordinary objects like Suger’s sar donyx chalice from Saint-Denis, and the most important Italian stained glass windows in America, the two-light Annunciation from Florence by Giovanni di Domenico. The Widener collection came to the National Gallery of Art on 9 September 1942. Because the gif t was contingent upon the entire collection being kept together, a portion of the ground floor of what is now the Gallery’s West Building was specially designed by David E. Finley, first director of the National Gallery, to house the decorative arts. 12 The collection went on public view on 20 December 1942.

The most extensive collection of stained glass that was formed by the Widener family, however, is now in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Purchased from Thomas and Drake by Joseph’s niece, Eleanor Widener Dixon, it comprised more than one hundred heraldic panels that she installed in her English Tudor mansion, Ronaele Manor, not far from Lynnewood Hall in Elkins Park. Many of these panels came from Wroxton Abbey, Oxfordshire, seat of the Popes and the Norths since 1537 following its dissolution. It was deeded to Trinity College, Oxford, in 1556, and leased back to the family until 1933 when it reverted to the college and the contents were sold off. Even the abbey now belongs to Fairleigh Dickinson University. 14 Other panels were bought up by Thomas and Drake between the wars, from the country houses of Ashridge Park and Cassiobury in Hertfordshire, and from the collection formed by Sir Thomas Neave at Dagenham Park, Essex.

Also in the Philadelphia Museum of Art is most of the glass acquired by America’s first dealer in medieval art, George Grey Barnard. Unlike other American collectors, Barnard had almost no money at all. Most of his life was spent dodging his creditors and trying to raise the funds to complete his sculptural project at the Pennsylvania state capitol. Barnard had the advantage of beginning to collect medieval art when there was virtually no competition. His first collection was sold, almost in its entirety, to John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and now forms the nucleus of the Cloisters collection. The second collection was sold after Barnard’s death in 1938 to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Barnard collected few examples of stained glass. There were only three pieces in his first collection. More pieces were included in his second collection, which he acquired after 925 ; most of that collection is now in storage in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Another collection that had entered this museum was also the victim of changing taste. More than fifty Swiss panels of the sixteenth century had been acquired by Dr. Francis W. Lewis from Dr. Ferdinand Keller of Zurich about 1880 and were given to the Philadelphia Museum of Art by his sister in 1907. They and a few other panels were sold at auction in 1947 and 1954.

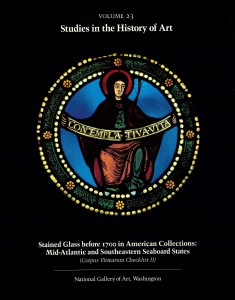

John Gellatly dedicated many years, and his own and his first wife’s fortune, to highly selective collecting, with public education in view; these pieces were to form the National Collection of Fine Arts (since incorporated into the National Museum of American Art ). First housed in his home in New York, at 34 West 57th Street, the collection was moved to the Heckscher Building on Fifth Avenue in 1928. In 1929, two years before his death, it was incorporated into the Smithsonian Institution, although it was not moved to Washington until 1933. A pioneer collector of American art, especially paintings by contemporaries such as Frederic Church, Thomas Dewing, and Abbott Thayer, Gellatly also had an unerring taste for medieval works. Totally unknown to scholars until now, these important pieces are in storage.20 They include a twelfth-century medallion, pronounced by Gellatly to be the finest in the collection, with a personification of the contemplative life, in almost perfect condition and in original leads, which appears to be associated with Chalons-sur-Marne. There are also several other choice pieces of French and English glass up to the mid-fifteenth century in date. Unfortunately, although the collector assiduously kept records of his acquisitions, these were lost at the time of his death; thus, not one panel carries a recorded provenance. The stock books kept by the English dealer Grosvenor Thomas and his son Roy have now revealed the immediate source of six of Gellatly’s pieces, however, which presumably passed through their New York office.

The Baltimore Museum of Art benefited indirectly from one of the largest collections of stained glass ever formed in the United States, that of William Randolph Hearst. Several important pieces were purchased by Saidie A. May at Gimbel’s department store in 1941 to decorate a Renaissance room that she had also bought from Hearst for the museum. In fact, she singlehandedly built the museum’s small but surprisingly comprehensive collection of Egyptian sculpture, African masks, European furniture, tapestries and carpets, and, above all, modern art.

These collectors have all contributed to the regional museums of the mid-Atlantic seaboard, with the result that, whereas in New England the most spectacular discoveries of important windows were made in churches, chapels, and private homes, here the great public collections, especially of the nation’s capital, have afforded the comparable surprises. The largest and finest collection, however, has only recently been given to an institution and opened to the public.

Raymond Pitcairn was probably the most extensive collector of medieval stained glass in America. That he purchased sixteen of the fifty-five lots in the Lawrence sale in 1921 is an indication of his competitiveness (the New York dealer Joseph Duveen buying a comparable number). In 1929, on the eve of the Depression, he acquired eight of the twenty-three twelfth- and thirteenth-century panels that appeared in Demotte’s catalogue; the other large buyer, with a taste for the glass of later periods as well, was William Randolph Hearst. In marked contrast to Hearst, Pitcairn’s focus in collecting was narrow, perhaps more so than that of any other American collector. Though his first purchase, made in 1916, was a piece of English grisaille glass, the collection, as it has evolved, is almost entirely French in origin. Very little is known about Raymond Pitcairn as a collector. It has been suggested that his interest in collecting medieval art began with his involvement in the building of Bryn Athyn Cathedral and that the stained glass and sculpture collections, the two largest of his holdings, were formed as exemplars for his work men in the decoration of the church. In fact, however, very few of the pieces in the collection ever served directly as models to be copied, and Pitcairn’s enthusiasm for his acquisitions, each of which was personally chosen, is made very clear in his correspondence. His intense feeling for art is that of the true collector. The Pitcairn collection remained in private hands and was inaccessible to the public until Mrs. Pitcairn’s death in 1980.

The Bob Jones University collection was formed from the first as an adjunct to the university; the intention was that it would be open to the public. Bob Jones II, a revivalist and fundamentalist preacher, formed a collection of religious art as a visual testimony to the literal interpretation of the Bible, the cornerstone of his beliefs. The emphasis is upon Renaissance and baroque painting, though the collection also includes a number of late medieval and Renaissance panels of stained glass. As Nathaniel Burt has observed, “It is a sort of cultural shock to see ensconced in this enclave of pure Protestantism the superb extravagances of emotional Catholicism.”

The McKean collection, now housed in the Morse Gallery in Winter Park, Florida, was begun in 1957 with acquisitions from the summer estate of Louis Comfort Tiffany at Oyster Bay, Long Island. In that year, a fire destroyed Laurelton Hall but the McKeans were able to purchase everything that was spared and thus founded one of the most comprehensive collections of Tiffany art in America.28 The collection includes work by Tiffany’s contemporaries and, since the focus is upon glass, a few examples of stained glass of earlier periods.

More elusive than collections, and therefore sometimes more intriguing to the hunter, are the single pieces of glass, often of very high quality, owned by individuals. One such case is the panel in Reading, Pennsylvania, discovered through a notice about the Corpus Vitrearum checklist that appeared in Stained Glass. It belongs to a retired glass painter who, no doubt like his predecessors during the Gothic Revival, has a high appreciation of the achievements of the medieval glaziers. Such a piece deserves to be more widely known. As noted in the introduction to the first volume of the checklist, in addition to the recognition of individual panels that add to our knowledge of medieval glazing programs, another great excitement of this kind of preliminary cataloguing is the rediscovery of connections between dispersed panels. Sometimes the distribution appears logical, given the fact that several of the collectors in America were acquiring glass from a small group of European dealers at about the same time. For instance, glass from Joseph Brummer was acquired by Pitcairn and by the Baltimore Museum of Art. On his death Brummer’s medieval collection was in part dispersed by auc tion, but the sizable balance was acquired from his sister-in-law, Mrs. Ernest Brummer, by Duke University. Other dealers frequently named in the checklist include Bacri, Heilbronner, Seligmann, Demotte, and Grosvenor Thomas.

Raymond Pitcairn purchased from Bacri two great thirteenth-century figures that almost certainly came from the choir clerestory of Sois sons Cathedral, while Walters acquired two others of the series from Heilbronner. The Corcoran Gallery of Art houses other glass from Soissons, though its early history is unknown. Composed of fragmentary medallions from the chapel windows, it adds to our knowledge of an ensemble that is also represented in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Two more pairs of seated figures acquired by Pitcairn and Walters, associated with the pair mentioned above but smaller in size, seem to have come from the royal Abbey of Braine by way of Soissons Cathedral after the French Revolution (Pitcairn acquired one from Bacri, who had also sold the Soissons glass to Mrs. Gardner in 1906). Companions to these figures are in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the St. Louis Art Museum. As in the case of Saint-Yved in Braine, the Burgundian church of Saint-Fargeau has been completely stripped of its early glass; much of it is in Geneva, but there are also fragments in the United States, at Wellesley College and in the Glencairn Museum. A mid-thirteenth century panel in the Baltimore Museum of Art belongs to a series, originating in Tours, of which others are in The Cloisters. Similarly, early four teenth-century glass from Evron is divided between the Glencairn Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Fifteenth-century canopies from Leoben in Austria are at Duke University and in the Walters Art Gallery. The source of two heraldic badges from Herst monceaux Castle, Sussex, passed unnoticed in the entries for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but larger remnants of this glazing have now been identified in Philadelphia and at Bob Jones University. There is a major work in the Philadelphia Museum of Art by the anonymous early sixteenth-century “Master of Saint John the Baptist,” who is represented in the last issue of the checklist by two exquisite heads. Some of the rare seventeenth-century decorative windows that once lit the cloister of Pare Abbey near Louvain are now installed in the Corcoran Gallery, while others that once graced the home of Henry Paine Whitney in New York are in storage at Yale University. Those in Washington give an ample idea of the delicate luminosity that could be achieved by a glass painter working from prints and in enamels.

Even small discoveries bring satisfaction. The border of a thirteenth-century panel in the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, documented by a nineteenth-century drawing when it was still in situ in Mantes Collegiate Church, has now been recognized in the Glencairn Museum. A well-preserved, thirteenth-century French figural panel at Duke University, complete with its decorative “mosaic” background and border, now finds a complement from the resolution of the lancet in the Glencairn Museum. Eventually it may be possible to identify other panels from this Genesis Window, and trace them to the original site.

Other such dispersals are already well known, such as the early nineteenth-century sales of glass from Saint-Denis and from the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris, both of which eventually benefited the Glencairn Museum in one case and the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the other. Panels in these collections have already been published, either in the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi volumes dealing with the glass of those famous monuments, or as addenda to them. Panels from a window in the Parisian Abbey of Saint-Germain-des Pres treating the life of Saint Vincent, now divided between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Walters Art Gallery of Baltimore, are also justly famous. There is a considerable bibliography for the early thirteenth-century panels from a window in Rauen Cathedral that dealt with the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, though its reconstruction has only recently been worked out in detail. Panels catalogued here in Glencairn are complemented by those in the Worcester Art Museum and in The Cloisters.

Each panel of glass included in Checklist II has been examined and catalogued by a member of the American Committee of the Corpus Vitrearum. If close examination was not possible, this has been noted. As in the case of Checklist I, omissions will probably be inevitable. The authors will be grateful if readers aware of these will contact them so that oversights can be remedied in an Addendum to Checklist IV.

Jane Hayward

The Cloisters

President, Corpus Vitrearum (USA)

Madeline H. Caviness

Tufts University

Vice President, International Board, Corpus Vitrearum